North of Echenzell near Ingolstadt, you don't even have to dig half a meter deep to come across finds from ancient times. This can be seen in a teaching excavation under the direction of junior professor Dr. Nadin Burkhardt (Professorship of Classical Archaeology at the KU) using the example of a former Roman overland road. The framework for the field research, in which students, pupils and volunteers participated, was the anniversary of the municipality of Wettstetten. Its former mayor Hans Mödl and mayor Gerd Risch had initiated the investigation of the road north of the Echenzell district. Further partners of the excavation were the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation, the Historical Association of Ingolstadt, the Ingolstadt City Museum and the Society for Archaeology in Bavaria.

The road was built by the Romans in the second century AD. Today, it still cuts straight through the landscape, still bears the name "Römerstraße" (Roman road) on maps and is also found in the coat of arms of the municipality. "This shows how present it still is in the consciousness of the population and helps to shape the identity of the community," explains Prof. Burkhardt. The road was built – along with the Limes – by the Roman military for the army. It connected the fort Pfünz near Eichstätt with the fort in Kösching, about 12 miles away. "With our excavation, we want to examine how well the body of the road is preserved, how it was built and whether different phases of use can be identified," says Burkhardt. For the students, the teaching excavation was also part of their practical module, in which they could acquire skills in excavation techniques and documentation methods.

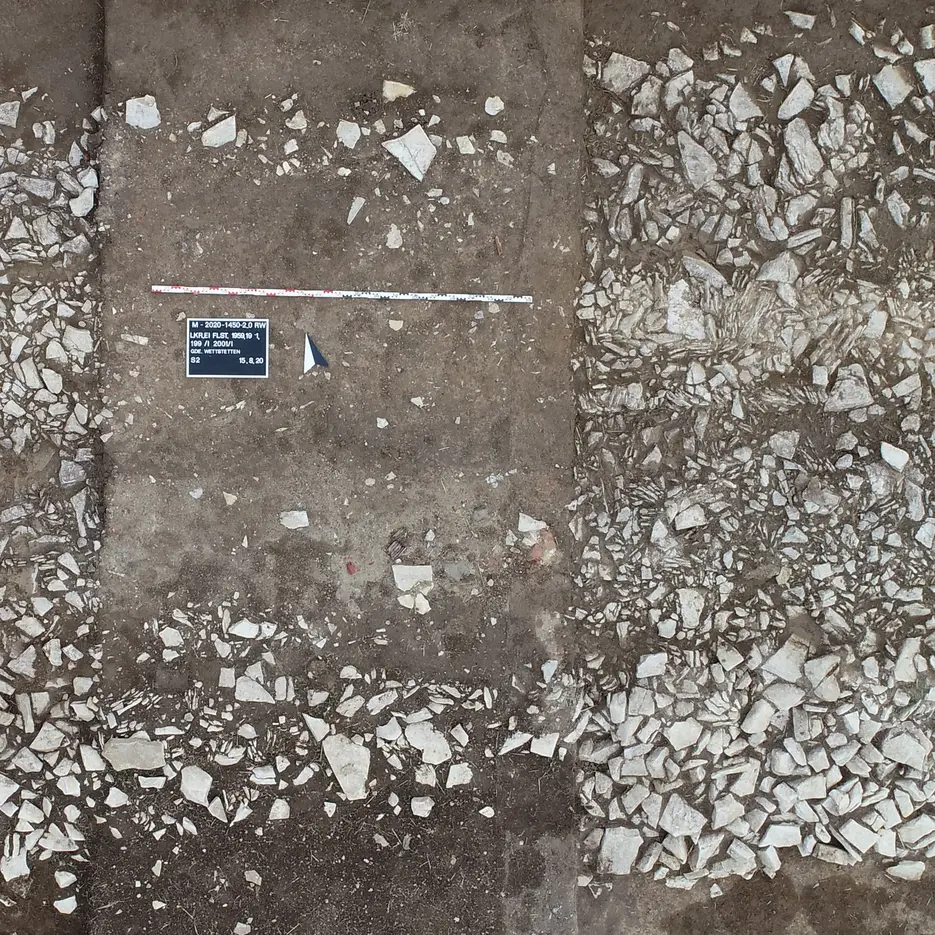

The excavation team of around 20 people was given three weeks to open up today's agricultural path at two selected sections and to explore the soil. Local residents also helped in the search for suitable sites. For example, Hans Mödl told the researchers about the remains of a limestone pavement that had been covered with a layer of gravel two decades ago to make the path better accessible for agricultural machinery. In a first step, an excavator pulled the top layer aside for the researchers, all further steps were done by hand. The antique road surface came to light after only 15 inches. Then the participants set to work on the fine details, which they also gave the population an insight into during an action day: Using trowels and spatulas, they exposed the top layer of clay and limestone pavement inch by inch. The material collected in the process was then sieved again to ensure that no small finds were overlooked. The finds range from Late Neolithic tool cuttings and core stones to Bronze Age vessel shards, Roman sandal nails, and Late Medieval to modern pottery. However, the team did not come across a belt of a variety of artifacts that is usually found around settlements from Roman times. This is consistent with the fact that no Roman settlement has been recorded in the vicinity of the excavation site and that Roman farms were also located further away.

However, the excavation did not only examine the surface of the former road, but also its structure. To this end, the researchers dug a cross section in both areas. This revealed that the path was still in use even before its current use: "The condition of the road and the pavement indicate that it was in use long after the forts no longer existed. The ancient layer was covered with a layer of clay in the course of further use. As the cross section shows, the lanes are deeply buried in the body of the road," describes Prof. Burkhardt. At first glance, the stone pavement of the road appeared to be arranged disorderly and shifted; some of the stones even stood upright. The archaeologist assumes, however, that heavy equipment was moved along the road in later times and crushed the stones: "In general, the Romans worked very professionally in road construction by using several layers of different stone sizes. This road was also built in several layers on a clay bed", says Burkhardt. Stones were probably also placed at an angle for side mounting, but just like a ditch alongside the road, as was usually common, these can no longer be traced. The Romans were very pragmatic in their search for materials – not only in the then province of Raetia – and used unprocessed limestone from quarries in the surrounding area. In addition, a high proportion of pebbles was found, which probably served as additional pavement. The iron-clad wheels caused clearly visible discoloration in the lanes.

Meanwhile, the two excavation sites on the Roman road near Echenzell were closed again. However, the knowledge gained will be presented to the population with a permanent display board along the road.