On behalf of the University Library, the historian has spent two years meticulously indexing and cataloging nearly 30 medieval codices that belong to the holdings of the Eichstätt Episcopal Seminary. The Seminary’s holdings are in the care of the University Library. Dr. Sabine Buttinger was able to assign the majority of the 30 manuscripts to the former Augustinian canonical monastery of Rebdorf, either by their ownership entries or the type of binding. In addition, there are volumes donated to the seminary by the cathedral library (Dombibliothek) to the seminary as well as eight volumes from Southern Germany and Austria, whose path to the seminary’s holdings can no longer be traced back.

Historical information galore: Searching for details in medieval manuscripts

![[Translate to Englisch:] Gruppe Handschriften](/fileadmin/_processed_/e/b/csm_Handschriften_Priesterseminar1_273677dc17.webp)

At the same time, the catalog shows the nearly complete indexing of the entire holdings of about 450 medieval manuscripts held by the University Library. “The fully indexed collection of the Seminary that is freely accessible online, now provides a basis for further research,” says Dr. Heike Riedel-Bierschwale, head of the section Historical Collections at the University Library.

For some volumes that seem unremarkable in terms of content, allow the reader to make interesting cross-connections. For example, among the newly indexed collection is a codex, which at first glance is a school manuscript on Latin grammar. However, the manuscript takes on greater importance when taking into account a scribe’s note referring to Johannes Permetter de Adorf, the first holder of a doctorate of theology at the University of Ingolstadt. In 1453, he began studying at the Faculty of Arts in Leipzig, he then went on to study theology in Heidelberg and Erfurt and finally got the academic title of Baccalaureus theologiae in Leipzig. He subsequently enrolled at the newly established University of Ingolstadt in 1472, where he received his doctorate in 1473. He stayed at the University as a full professor and died in Ingolstadt in 1505. The manuscript was likely purchased by the Rebdorf monastery in the 15th century.

“Every manuscript gives us historical information galore. It is a tremendous privilege to work with such collections,” says Buttinger. They provide us with an insight into a time long gone that continues to have an impact on our present day life. For instance, one of the books from the collection is highly relevant to historical research. A simple parchment fascicle provides a direct view of Bishop Johann III von Eych (1445-1464) and his comprehensive reform efforts in the Eichstätt diocese, which were carried out in implementation of the Basel reform decrees. The parchment shows a meticulously executed letter that Johann von Eych wrote in 1457 to the Benedictine nuns of St. Walburg, who had stubbornly resisted refom until 1456. It contains a detailed overview of the turbulent and conflict-ridden events, which makes this letter an important source of the clerical and monastic reforms in the 15th century. The fascicle in the University Library is the sixth copy of the Bishop’s letter still in existence.

On the other hand, the library catalog, which was started in the late 15th century and kept well into the 16th century, shows the importance that the Rebdorf monastery attached to studies and care of books. The vast majority of the approximately 1000 works listed here were added to the constantly growing library during the heyday of Rebdorf under Prior Kilian Leib (1503-1553). With its large number of pages, generous gaps and numerous leaves already provided with titles, the library catalog had the potential to hold many more titles. This shows that the creator’s planned for more.

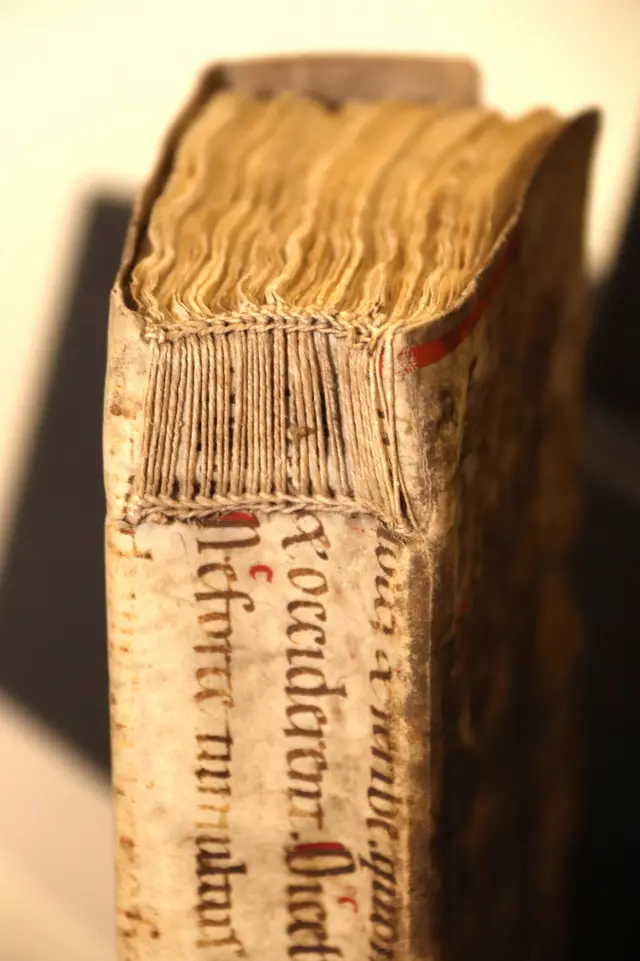

![[Translate to Englisch:] Recycling](/fileadmin/_processed_/a/5/csm_Handschriften_Priesterseminar7_dcfa3a936f.webp)

This 15th century book is a curiosity even at first glance due to its tiny size: It easily fits into the palm of a hand. On wafer-thin parchment it contains, among other things, the Rule of St. Benedict in miniature script. The saints Rupert and Virgil that are named in the Litany of the Saints might point to the archdiocese of Salzburg. The overall condition of the volume, which has a leather-covered wooden binding and tiny metal clasps, suggests that this book, despite its handy format, might not have been an object of daily use, but an intriguing curiosity. Maybe even producing and possessing such an item were a form of worship.

“Every manuscript is unique. Every time I am amazed anew at the treasures that are unearthed when our holdings are catalogued, and at the world that they open up as a result,” says Michael Wohner, the rector of the Eichstätt Seminary.

The Catalog giving an overview of the holdings of the Eichstätt Seminary is online accessible at www.ku.de/bibliothek/suchen-und-finden/sammlungen/handschriften-nachlaesse.

![[Translate to Englisch:] Ein allein schon optisch kurioses Stück des Bestandes ist ein Band aus dem 15. Jahrhundert, der gerade mal in eine Handfläche passt. Auf hauchdünnem Pergament findet sich darin in Miniaturschrift unter vielem anderem die Benediktregel.](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/5/csm_Handschriften_Priesterseminar4b_7b37de7c23.webp)