- English

- Deutsch

- Französisch

Prince Max of Saxony Endowed Chair for Theology of the Christian East (2018–2023)

Back to the homepageThe establishment of the Prince Max of Saxony Endowed Chair for Theology of the Christian East by the Diocese of Eichstätt is closely linked to the history of the Collegium Orientale. Since its foundation in 1998 the interest in theology of the Eastern Churches has steadily increased in Eichstätt along with the growing number of students from the various churches of Eastern rites. Acting on the initiative of the Collegium Orientale, the Diocese of Eichstätt instituted a Chair for Theology of the Christian East within the Faculty of Theology of the Catholic University Eichstätt-Ingolstadt, which was inaugurated on October 1st 2018. The chair is named after Prince Max of Saxony who seems to be predestined for it in many respects: He was a graduate of the Episcopal Lyceum in Eichstätt, was ordained a priest in the Schutzengelkirche (Church of the Guardian Angels) in Eichstätt, was a teacher of Eastern Church Studies with an exceptionally broad knowledge of the Christian East, and a passionate pioneer of ecumenism. He also maintained excellent contacts in Lviv, Ukraine, from where a large number of students attend the Eichstätt Faculty of Theology today. In addition, his estate is kept in the archives of the KU Eichstätt-Ingolstadt, and is accessible there for research purposes.

Prince Max of Saxony

Biography

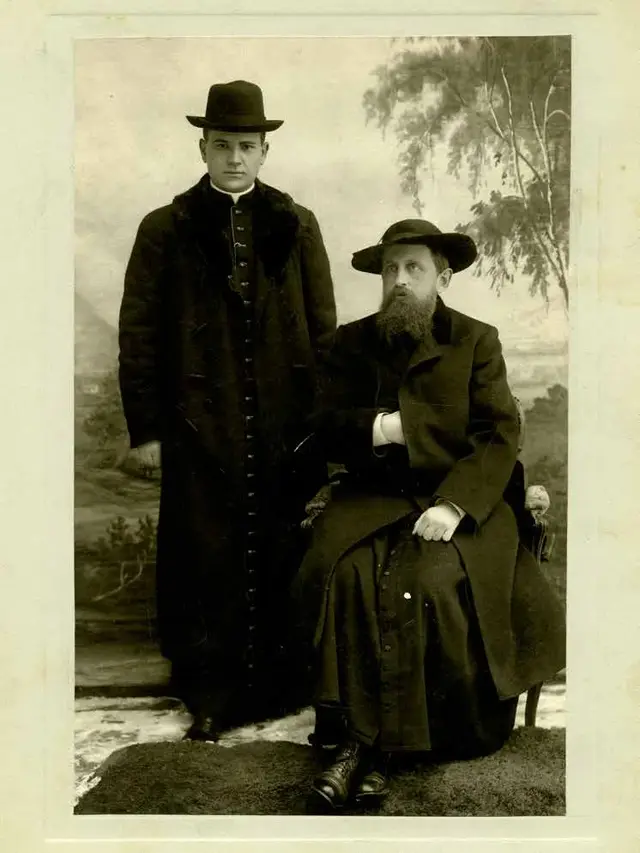

Prince Maximilian of Saxony was born the third son of Prince George, Duke of Saxony (King of Saxony since 1902), and Maria Anna, née Infanta of Portugal (1843-1884), in Dresden on November 17th 1870. After his childhood and youth at the royal court in Dresden, he completed his military service in 1888/1889. He then studied law, history, and political economics in Freiburg i.Br. and Leipzig, and was awarded a doctorate of both laws in Leipzig in 1892. From 1893 to 1896 he studied philosophy and theology at the then Episcopal Lyceum Eichstätt, the predecessor institution of today’s Catholic University Eichstätt-Ingolstadt, and lived in the Episcopal Seminary. On July 26th 1896, he was ordained a priest in the Schutzengelkirche in Eichstätt by Dresden’s Apostolic Vicar Ludwig Wahl, and renounced his claim to the royal throne of Saxony on the day of his First Mass in Dresden.

This was followed by a short pastoral assignment in Whitechapel/England and in St. Walburg in Eichstätt. After several months at the University of Würzburg, he was awarded a doctorate in theology in the autumn of 1898. From 1898 to 1900 he was chaplain at the Frauenkirche in Nuremberg, where he lived very modestly and passed on his endowments from the Saxon royal family to the poor. In 1900, Max of Saxony was appointed to the Faculty of Theology at the University of Fribourg/Switzerland as associate professor, and from 1908 as full professor at the chair of Canon Law and Liturgy, which he held until 1911. From 1910 to 1914, he lectured at the seminary of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in Lviv on the liturgical rites of the various Eastern Churches. From 1912 to 1914, he also taught liturgy at the Catholic seminary in Cologne.

During the First World War, Max of Saxony was deployed as a field and hospital chaplain on the Western Front in Belgium. Under the impression of the horror and the German war crimes against the Belgian civilian population, he turned pacifist. Among other things, he denounced the Armenian genocide of 1915. He left the military service in June 1916, and remained in Saxony for pastoral care and studies, interned in the Old Hunting Lodge in Wermsdorf. He continued to work towards a theology of peace; he also devoted himself to animal rights and was himself a vegetarian, teetotaller, and tobacco opponent. After the First World War, he gave lectures on peace, life reform, vegetarianism, and animal rights in many cities until 1937. Early on, he publicly warned against the rising National Socialism and anti-Semitism.

From 1921 onwards, Prince Max taught again in Fribourg at the Faculty of Philosophy, where he was given a post as lecturer in Oriental Cultures and Literatures. In 1923/24, he was dean of the faculty. He was made emeritus professor in 1941, but continued to work as an honorary professor. Owing to his appearance and his shabby clothes because of his frugality, he was considered one of the most striking personalities of the city in his old age. Max of Saxony died on January 12th 1951 after a short illness in a Fribourg hospital, and was buried in the cemetery of the Canisius Sisters in Bürglen, whose house chaplain he was, to outpourings of sympathy from the population.

Cf. the German-language Wikipedia entry “Maximilian von Sachsen (1870–1951)”.

Prince Max as a lecturer in Eastern Christian Studies

Early Interest in Eastern Christian Theology

In 1900, Prince Max started his teaching role as Professor in Swiss Fribourg, and became outstandingly familiar with the Christian East. This interest of Prince Max had awoken almost overnight early on in his time teaching in Fribourg, but quickly became one of the most essential leading principles of his scientific work and life. At the same time, he voiced his hope for reconciliation and reunification of the churches – in a time in which a renewed interest in Eastern Churches grew in the West under Pope Leo XIII., strongly connected with thoughts of reunification of the Churches of East and West.

Prince Max’ reference point were Liturgical Studies. His method of comparing the liturgical texts and forms of expression of East and West was practiced by few at the time. Naturally, this required solid knowledge of Oriental Liturgical Studies and Philology, which Prince Max acquired early on. To this end, he learned Russian, Church Slavonic, Syriac and Armenian.

Oriental Journeys as Moments of Encounter

Enthusiasm for the life and spirituality of oriental churches, especially in experiencing liturgy and art, and primarily the question of overcoming the division of Christianity motivated Prince Max with great passion. Therefore, he undertook five major journeys into oriental and Eastern European countries between 1903 and 1909, in the course of which scientific aspects were combined with concrete experiences: He attended church services, maintained ecclesial and political contacts, explored public and private libraries and collections, and prayed for the unity of the church. His five journeys appear as five targeted expeditions to the most important sites of Eastern Christianity, in which the Saxon prince developed a particular liking for Armenia and Ukrainian Galicia. Methodically, he developed a broad, representative image of the many facets of the Christian East, which is without parallel, not just in its own time.

Ecclesial Experience

The Prince’s main interest during his journeys lay in the experience of Eastern Church liturgies, in which he learned to appreciate oriental expressions of faith in their various facets from an inside perspective. Before, he had explored Liturgical Studies based on editions of liturgical texts. The immediate experience of the beauty and difference of Eastern Church liturgies and their art is the key through which Prince Max found his way into Eastern Church theology. This differentiated him not just externally from the “study hall scholars” of his time. Without expressly reflecting upon that, he pursued a hermeneutical approach which only developed its full potential within Orthodoxy later on, where more modern Orthodox theology began to see itself as theological reflection of ecclesial experience. Even today, ‘experience’ does not simply mean individual incidents. Experience is understood to mean living the liturgies and asceticism which is practiced by the church. The holistic approach is therefore essential.

The Turning Point: “Thoughts on the Question of Church Unity”

Prince Max articulated his vision for the restauration of Christian unity in the journal of Grottaferrata Abbey in 1910. It garnered great attention because it seemed irreconcilable with Roman thought at the time, and held explosive power due to its ecumenical convictions – some of which began to be shared by the Catholic Church in the Second Vatican Council, whereas some are still not accepted. The Prince was far ahead of his times in this. Pope Pius X. distancing himself from Prince Max in a document, and prohibiting him from sharing certain convictions was seen as decisive, and interpreted by many as a revocation of his permission to teach. It is arguably the most tragic incision of his life.

Prince Max, however, was convinced of his intentions and also left no doubt about his loyalty to the Catholic Church. In retrospect, his thoughts can be understood as a "pre-ecumenical vision" that strove for the right understanding of church unity, although the Saxon prince also spoke of the mistakes of the Catholic Church in the past 1000 years with great frankness and to general displeasure. In doing so, he also expressed the remarkable conviction that Orient and Occident had never been completely separated anyway and that the divisions were ultimately due to political motives and misunderstandings fuelled by jealousy and hostility, so that the restoration of full unity was possible through repentance on both sides and reconciliation. Despite, or precisely because of, his excellent relations with the Greek-Catholic Metropolis of Lviv, Prince Max was a firm opponent of the Catholic Church's Uniatism, since it did not sufficiently respect the equal dignity of the other and curtailed the other's autonomy too much. Particularly noteworthy in this context is the use of the term "sister churches", which had already emerged in the 5th century, but later experienced little reception and only played a central role again in ecumenical efforts since the time of the Second Vatican Council, but here was used programmatically by Prince Max.

Teacher of Eastern Church Theology in Galician Lviv

While Prince Max suffers the greatest crisis of his life, he finds inner peace and human recognition again in Lviv in Galicia. There, Catholics of the Byzantine rite enjoyed high esteem under the Habsburg monarchy. For four years (1910-1914), Prince Max lectured in German on Eastern Churches at the Greek Catholic General Seminary in Lviv, at the invitation of the head of the Ruthenian Greek-Catholic Church, Metropolitan Andrej Scheptyzkyj, himself also a "prophet of ecumenism.” While his special interest in Eastern Church theology made him exotic in the Swiss Üechtland, and only a few students found their way to him, he met with lively interest among the seminarians in Lviv. At the same time, he also lectured at the Cologne seminary.

With the First World War, the tide turned again for the Saxon prince. He had to interrupt his teaching and was appointed field chaplain, but was interned in Wermsdorf Castle because of his outspoken expression of pacifist thoughts. This, however, benefited his scientific work. He had enough time until the end of the war and beyond to work on texts of the Church Fathers and the translation of ancient Eastern liturgies.

Fribourg again

The shattering impressions of the First World War led to Prince Max' areas of interest shifting. While Eastern Church theology receded somewhat into the background, he devoted himself all the more intensively to pacifist thinking, which he reflected in his distinctive ethics of peace and creation. In 1921, he returned to Fribourg, Switzerland, where he continued to teach at the Faculty of Philosophy. He received a teaching assignment for "Oriental Literature and Culture" and worked in this field until shortly before the end of his life in 1951. During this time, his subjects covered the history, culture and theology of the Christian East in its full breadth: Prince Max dealt with the individual Eastern Churches and their liturgies, Eastern Church Fathers and their works, ecclesiastical poetry of the East, regional geography and much more.

The Prince’s Legacy

What is fascinating about Prince Max of Saxony to this day is the uniqueness of his attitude towards the Churches of the East. Perhaps it is not the detail or the level of his scholarly erudition, which has sometimes been questioned, even though he was undoubtedly immensely well-read, possessed excellent linguistic skills and admirably compiled the available material. Rather, his entire life's testimony is a single authentic unity. This unity includes an irrepressible enthusiasm and love for the Churches of the East, their rich traditions and their spiritual depth. From this ecclesiastical experience he was able to develop – far more than many of his Orientalist colleagues – the passionate struggle for the unity of Christianity with which he far surpassed his contemporaries. Prince Max's impulses for a renewal of attitudes towards Oriental Christianity are extraordinary. His legacy is based on an existential mutual appreciation, testifies to the value of what he personally experienced and learned, inspires encounters with members of sister churches, encourages the study of the rich Eastern heritage in all its facets, and boosts the passionate ecumenical commitment to Christian unity.

This passage is the translation of an excerpt from:

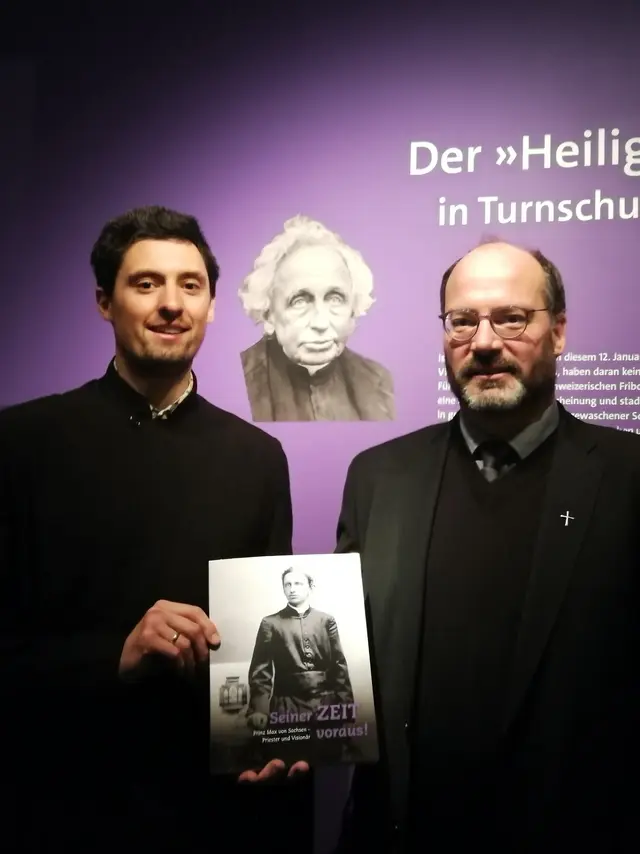

Thomas Kremer / Miriam Raschka / Ruslan Stetsyk: Prinz Max von Sachsen und die Ostkirchen [Prince Max of Saxony and the Eastern Churches], in: Iris Kretschmann / André Thieme (Hgg.), Seiner Zeit voraus! Prinz Max von Sachsen – Priester und Visionär (Sonderausstellung im Schlossmuseum Pillnitz vom 13. April bis 3. November 2019) [Ahead of his time! Prince Max of Saxony –Priest and Visionary (Special Exhibition in the Palace Museum Pillnitz)], Dresden 2019, 76–99.

Catalogue of the Prince's works

In addition to numerous handwritten and typed manuscripts that are only preserved in archives, the following works by Prince Max of Saxony are easily available in libraries:

- Die staatsrechtliche Stellung des Königlich Sächsischen Markgrafentums Oberlausitz, Dissertation, 1892. [60 S.]

- Vertheidigung der Moraltheologie des hl. Alphonsus von Liguori gegen die Angriffe Robert Grassmann’s, Nürnberg 1899 und weitere Auflagen. [58 S.]

- Der heilige Märtyrer Apollonius von Rom. Eine historisch-kritische Studie, Dissertation, Mainz 1903. [VI, 88 S.]

- Das Erlösungswerk Jesu Christi. Predigten geh. in d. röm.-kath. Kirche zu Thun, 23.–27. Febr. 1906, Fribourg/CH 1906. [109 S.]

- Die Vereinigung der Seele mit Jesus Christus. Geistliche Abhandlungen vom hl. Alfons Rodriguez, hg. von Max, Herzog zu Sachsen, Freiburg i. Br. 1907. [XV, 288 S.]

- Vorlesungen über die orientalische Kirchenfrage, Fribourg/CH 1907. [VIII, 248 S.]

- Übersetzung des griechischen Offiziums vom Karsamstag (Epitaphia) ins Französische, 1907.

- Missa Syriaca-Antiochena. Quam ex lingua Syriaca in idioma Latinum traduxit cum commentario praevio (Ritus missae ecclesiarum orientalium Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae unitarum; 5), Regensburg 1908. [XIV, 54 S.]

- Weitere Übersetzungen orientalischer (syrisch-maronitisch, chaldäisch, griechisch, armenisch) Messriten ins Lateinische, 1907/08.

- Was muß der Mensch tun, um sich der Erlösung Jesu Christi teilhaftig zu machen? Kanzelvorträge, Regensburg 1908. [IV, 92 S.]

- Predigten über das erste Buch Mosis von Max von Sachsen gehalten während der Fastenzeit in der Liebfrauenkirche zu Freiburg (Schweiz), 6 Bde., Bd. 1.: Von der Erschaffung der Welt bis zur Sündflut, Fribourg/CH 1908; Bd. 2: Von der Sündflut bis zum Bunde der Beschneidung, Fribourg/CH 1910; Bd. 3: Von der Verkündigung der Geburt Isaaks bis zu dessen Vermählung, Fribourg/CH 1910; Bd. 4: Von Abraham's Tod und der Geburt der Zwillinge Esau und Jakob bis zur Versöhnung Jakob's und Laban's, Fribourg/CH 1911; Bd. 5: Vom Einzug Jakobs ins gelobte Land bis zur ersten Reise seiner Söhne nach Ägypten ausschließlich, Fribourg/CH 1913; Bd. 6: Vom Einzug der Kinder Israels nach Ägypten bis zum Ende des ersten Buches Mosis, Fribourg/CH 1913. [226, 268, 267, 262, 260, 226 S.]

- Praelectiones de liturgiis orientalibus, habitae in Universitate Friburgensi Helvetiae a Maximiliano, principe Saxoniae, Bd 1: Continens: 1. Introductionem generalem in omnes liturgias orientales. 2. Apparatum cultus necnon annum ecclastiasticum Graecorum et Slavorum, Freiburg i. Br. 1908; Bd. 2: Continens liturgias eucharisticas Graecorum (exceptis Aegyptiacis), Freiburg i. Br. 1913. [VII, 241; VII, 362 S.]

- Pensées sur l’union des Eglises, in: Roma e l’Oriente 1 (1910) 13–29; deutsche Übersetzung: Gedanken des Prinzen Max, Königliche Hoheit, Herzogs von Sachsen, über die Vereinigung der Kirchen, in: [Natalie] Baronin von Uxkull [Uexküll]: Rom und der Orient [1.] Jesuiten und Melchiten, Pormetter 1916, 67–90.

- Des Heiligen Johannes Chrysostomus Homilien über das Evangelium des heiligen Matthäus, 2 Bde., Regensburg 1910/1911. [XII, 697, IV, 621 S.]

- Vorbilder Mariä. Maipredigten ... gehalten in der Liebfrauenkirche in Freiburg (Schweiz); neun Jahrgänge in einem Band, Fribourg/CH 1911.

- Des Heiligen Johannes Chrysostomus Homilien über die Genesis oder das erste Buch Mosis, 2 Bde., Paderborn 1913/14. [X, 966; 320 S.]

- Erklärung der Psalmen und Cantica in ihrer liturgischen Verwendung, Regensburg 1914. [528 S.]

- Das christliche Hellas. Vorlesungen gehalten an der Universität Freiburg (Schweiz) im Sommersemester 1910, Leipzig 1918. [362 S.]

- Dreifaltigkeitslieder, Dresden 1918. [168 S.]

- Messgesänge, Dreifaltigkeits- und Auferstehungslieder, Dresden 1918. [504 S.]

- Nerses von Lampron. Erklärung der Sprichwörter Salomos, 3 Bände, 1919–26.

- Ratschläge und Mahnungen zum Volks- und Menschheitswohle, Dresden 1921. [89 S.]

- Nerses von Lampron. Erklärung des Versammlers, Leipzig 1929. [187 S.]

- Der heilige Theodor. Archimandrit von Studion (Religio; 1), München 1929. [95 S.]

Digitised heritage and collection of material

This page is still under construction.

Research contributions of the Chair

Employees and students of the Endowed Chair Prince Max of Saxony are engaged in research on the history and legacy of the eponymous Prince. Thus far, the following contributions have been published or are in preparation:

- Thomas Kremer / Miriam Raschka / Ruslan Stetsyk: Prinz Max von Sachsen und die Ostkirchen [Prince Max of Saxony and the Eastern Churches], in: Iris Kretschmann / André Thieme (Hgg.), Seiner Zeit voraus! Prinz Max von Sachsen – Priester und Visionär (Sonderausstellung im Schlossmuseum Pillnitz vom 13. April bis 3. November 2019) [Ahead of his time! Prince Max of Saxony –Priest and Visionary (Special Exhibition in the Palace Museum Pillnitz)], Dresden 2019, 76–99.

- Thomas Kremer: Prinz Max von Sachsen und seine Rede von den „Schwesterkirchen“ [Prince Max of Saxony and his Talk of Sister Churches], in: Daniel Munteanu (Hg.), „Ökumene ist keine Häresie“. Theologische Beiträge zu einer ökumenischen Kultur [„Ecumenism is no Heresy“. Contributions to an Ecumenical Culture], Leiden 2021, 513–528.

- Thomas Kremer: Protagonist einer liturgisch-mystischen Exegese Eichstätter Prägung. Die „Erklärung der Psalmen und Cantica in ihrer liturgischen Verwendung“ (1914) des Prinzen Max von Sachsen [Protagonist of a liturgical-mystical Exegesis of Eichstätt Influence. The „Explanation on the Psalms and Cantica and their Liturgical Use” (1914) by Prince Max of Saxony], in: Bernd Dennemarck u. a. (Hgg.), Prinz Max von Sachsen. Menschlich – Aufrichtig – Nachhaltig [Prince Max of Saxony. Humane – Genuine – Lasting] (Fuldaer Hochschulschriften; 65), Würzburg 2021, 91–129.

- Joachim Braun: Prinz Max von Sachsen und Armenien. Eine vergessene Perspektive zur „Armenischen Frage“ [Prince Max of Saxony and Armenia. A Forgotten Perspective on the „Armenian Question“], in: Bernd Dennemarck u. a. (Hgg.), Prinz Max von Sachsen. Menschlich – Aufrichtig – Nachhaltig [Prince Max of Saxony. Humane – Genuine – Lasting] (Fuldaer Hochschulschriften; 65), Würzburg 2021, 159–182.

- Prinz Max von Sachsen als Lehrer der Ostkirchenkunde in Lemberg am Beispiel seiner Vorlesung zur Jakobusliturgie [Prince Max of Saxony as a Teacher of Eastern Church Studies in Lviv exemplified by his Lecture on the Liturgy of Saint James], Licentiate Dissertation from June 2021.